lans for the Green Era Community Area include an outdoor market space/community garden center where fresh foods and native plants will be sold to low income residents/visitors, at left, and a community education center behind (phase 2).

A Conversation with

Jason Feldman of Green Era

By Susan Messer

In April 2021, the One Earth Film Festival screened Closing the Loop, a documentary about the circular economy, and since then, I’ve been exploring the subject with the three experts from the post-film panel. In this interview, I spoke with Jason Feldman, co-founder of Green Era, a partnership working to bring green energy and jobs to Chicago’s Southside and at the same time to demonstrate the values of a circular economy.

In case you don’t remember, in the traditional linear economic model, when a resource serves its purpose, we throw it out, where it adds to the problem of landfill. In the circular economy, we give used materials a new purpose; we find ways to circulate them back into usefulness.

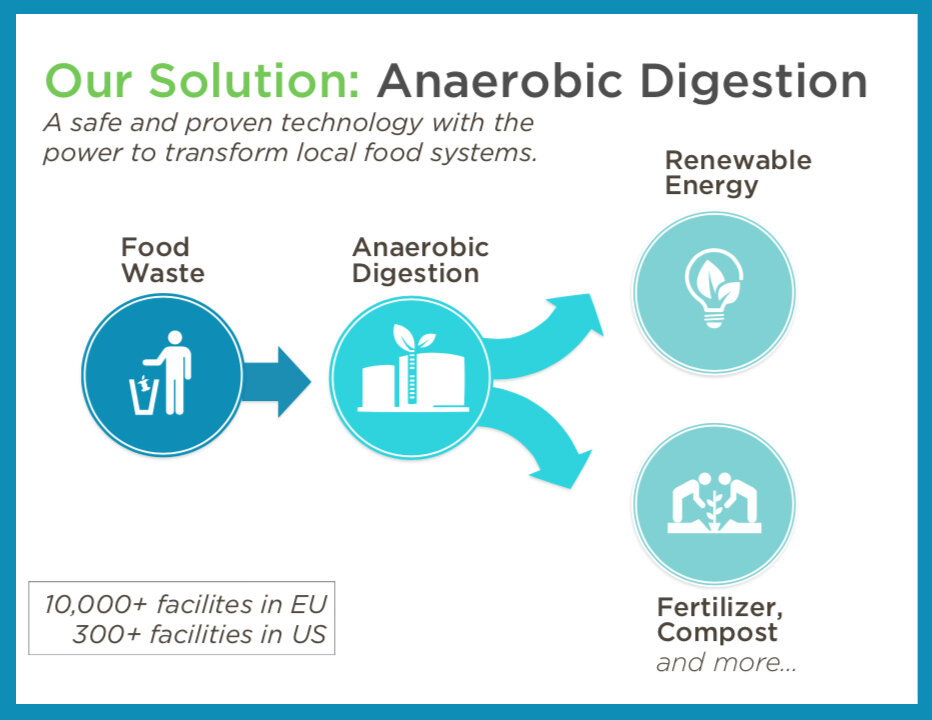

Green Era’s current project is a great model of the circular economy because it involves diverting inedible food waste from landfills and, via a process called anaerobic digestion, producing clean, renewable energy as well as nutrient-rich soil, which will then be used to expand fresh, local food production. All this will occur on a vacant, brownfield site in South Chicago, in an area with an urgent need for cleanup and economic development.

In August 2020, after a yearlong competition, Green Era, part of the Always Growing Auburn Gresham team, won the $10 million Chicago Prize to develop their vision of a healthy lifestyle hub and renewable energy and urban farming campus. In addition, Gov. J.B. Pritzker announced a $2 million investment from the state’s Rebuild Illinois program to fill the final funding gap for the Green Era Renewable Energy & Urban Farming Campus.

SM: Wow. Congrats. How did you get into this? It’s so huge.

JF: Green Era evolved from a long-time personal interest in urban farming and the positive impact it has on communities, and by working with Urban Growers Collective, a Black- and women-led nonprofit in Chicago that is working to build a more just and equitable local food system. Demand for locally grown food is increasing, but there is an inadequate supply of clean, healthy soil for use by local, urban growers and farmers. We also had research showing that crime was going down around urban farms. We thought, “How do we scale this up? How can we grow more urban food and expand the benefits to the community?”

Soil in Chicago (and in most urban areas) lacks nutrients and is contaminated with high levels of toxins and construction debris. Farmers need large volumes of soil to create new farms. In addition, after harvest, soil must be replenished because the crops absorb nutrients and reduce the volume of the soil. So, we knew we needed to scale up composting, and anaerobic digestion was the answer to meeting this need.

I’ve been studying the anaerobic digester industry for almost 10 years. The technology is proven and safe, but we had to develop it in a way that successfully worked both operationally and financially in an urban area. Plus, we have to make it easy for communities and organizations to divert the food waste for the digester.

SM: Sounds complicated.

JF: I have experience with complex projects, but this is a very heavy lift. There is a tremendous amount of engagement related to policy, energy, recycling, federal credits, community, and more. Plus, we were closing on financing just as COVID-19 hit. It’s been a very difficult year. The big waste industry is an established business, and change (particularly in recycling) does not typically happen quickly. However, that also creates opportunity for new businesses. For example, we’re working with a local minority hauler (the only minority hauler in the City of Chicago), and this is an opportunity for them to expand their routes and diversify their business. We’re also working with various large food and beverage manufacturers and distributors to become suppliers for the digester.

The Green Era Renewable Energy & Urban Farming Campus will include the digester building and tanks at left, an urban farm at right, a community education center (phase 2) and an outdoor market space/community garden at front left.

SM: What about grocery stores? They must generate tons of food waste.

JF: Grocery stores want to recycle, but currently it is difficult to do so in a meaningful way. It’s easy to recycle clean produce waste, but there are few to no options to compost food waste in packaging and dairy and meat waste. There’s a lot to it: They have to remove packaging. They have to train staff about what can be mixed in and what can’t. For example, the salad bar at your grocery store might have meat and cheese in it, but many composters can’t take meat and dairy waste. So that batch of food waste might get rejected by the local composter. That’s where Green Era comes in. Our digester is unique because it has on-site de-packaging capabilities, which allows it to accept food waste in packaging. The digester can also process both meat and dairy wastes. Our goal is to make it easy and cost-effective for communities and organizations to recycle their organic waste and lower their carbon footprint. It’s a win for all.

SM: Please tell me more about the digester.

JF: It’s really just a fancy composter. It’s a big sealed tank. Food waste goes into the tank, which contains microorganisms that break down (or digest) the organic matter into biogas and digestate. The biogas is upgraded into renewable natural gas (a carbon-negative renewable energy) and digestate—a nutrient-rich compost material that will go to local urban farms.

SM: But the project has more to it than composting and energy production, correct?

JF: Yes, we’re also creating an on-site educational center, to provide hands-on STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) education around recycling, green energy, local food production, healthy eating, and new entrepreneurial opportunities. STEAM education in underserved communities is key to building the new green economy in a just and equitable way. We want young people to see the whole lifecycle of the process and how the Green Era closed-loop system of recycling organics while also creating renewable energy and nutrient-rich compost can benefit the community, local food systems, the environment, and economic development.

We’ll also provide training and employment opportunities in a low-income area that sustained a disproportionate impact from decades of disinvestment and industrial pollution. The pandemic showed us how fragile our food system is, so the time is right to empower communities to grow and distribute food locally. The benefits of this catalytic new green industry are meaningful and measurable, and we’re excited to be part of this important transition.

Jason Feldman

SM: Where do things currently stand with this project?

JF: The project is being developed on a vacant, brownfield site. The first step was to clean up the property. The facility is now currently under construction, and we anticipate opening early next year.

To learn even more about the circular economy, sign up for “What in the World is a Circular Economy?” sponsored by the Forest Preserves of Cook County from 12 to 1 p.m. Wednesday, Aug. 18: https://fpdcc.com/event/what-in-the-world-is-a-circular-economy/

This article is part three of a series of three articles on the Circular Economy. Find the first two here:

Article 1: A Conversation with Jonathan Pereira of Plant Chicago

Article 2: A Conversation with Thomas Fecarotta of Rheaply