Little Brown Book Group

By Laurie Casey

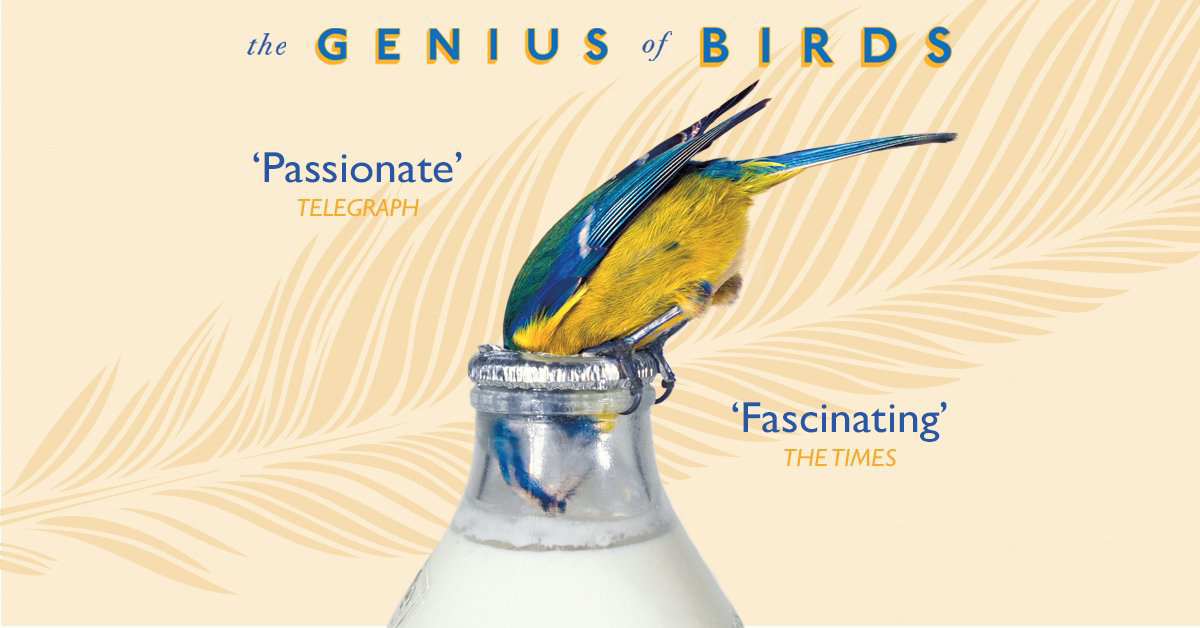

If you’ve ever wondered about pigeons’ navigational abilities, parrots’ linguistic skills or the musical memory of mockingbirds – and even if you haven’t -- it might be time to pick up a copy of The Genius of Birds by Jennifer Ackerman.

You’ll have a chance to discuss this book at the upcoming Nature Book Club, presented by Chicago Audubon Society and Trailside Museum at 7 p.m. Thursday, May 17, at Trailside Museum of Natural History, 738 Thatcher Ave., in River Forest. Ages 14 & up. Call 708-366-6530 for details.

Ackerman, an accomplished science writer who has tackled the human body, the common cold, and heredity in previous books, turns her considerable writing skills to the subject of birds. She gathers rich reporting about the latest ornithological research, her own first-hand observations and a colorful writing style to pull together this engaging book about avian intelligence.

“What kind of intelligence allows a bird to anticipate the arrival of a distant storm?” asks Ackerman. “Or find its way to a place it has never been before, though it might be thousands of miles away? Or precisely imitate the complex songs of hundreds of other species? Or hide tens of thousands of seeds over hundreds of square miles and remember where it put them six months later?”

As anyone who has ever searched for the glasses sitting on the bridge of their nose can attest, this intelligence is distinctly avian. Bird brains developed on a unique trajectory because they descended from dinosaurs. Through history, “while our neurons were sorting themselves into cortical layers to generate complex behavior, birds were devising another neural architecture altogether, different from a mammal’s but – in some ways, at least – equally sophisticated,” says Ackerman.

Each chapter of The Genius of Birds tells the story of bird species with extraordinary intelligence. The reader learns about crows, chickadees and sparrows, as well less familiar species with fascinating characteristics. The western scrub jay, for example, remembers not only where it buried food for later eating, but also what kind of food (nuts, seeds, fruit, insects and worms) and when, so the bird can find and eat each food before it spoils. (Another way that birds show us up: sadly, most Americans can’t find food in their own refrigerators before it spoils. But I digress.)

The final chapter tries to answer the question: which birds may survive climate change, and why? As the Audubon Society estimates that up to half of all bird species will go extinct, this is a crucial question.